For the better part of a decade, John Cleese had a recurring role as the A.D. White Professor-at-large, at Cornell University. And, by “role”, I mean faculty gig. During that time he met David Dunning and became enamored with his research – as many of us have. As a communicator though, Cleese, is the antithesis of most academics. Academics excel at contorting straightforward ideas until they are no longer recognizable, with logic so tangled it is nearly impossible to follow. Cleese, like so many great writers (especially comedy writers) has a gift for rendering the complex, blindingly obvious. And concise. And Pithy. And very funny. In a conversation with Eric Idle, he explained Dunning’s findings brilliantly:

“In order to know how good you are at something requires almost exactly the same skills as it does to be good at it in the first place. So if you’re absolutely no good at something, you lack exactly the skills that you need to know you’re no good at it.”

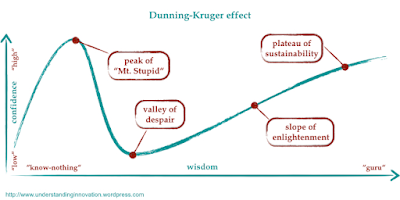

The Dunning-Kruger effect is fairly well-known now. It has reached the public consciousness in internet memes like:

There is a sort of common-sense-ness about all of this. We all know that person who is certain of their rightness or superior skill – who confidently mansplains it all to people far more competent than themselves, oblivious to the fact that, the more they talk, the more they come off as a prick. Many of us have been that person and, once we develop some actual competence, look back on things we have said or done with embarrassment over our naive arrogance. The Mt. Stupid meme resonates with timeless wisdom about the hubris of beginners and humility of experts. “The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubts, while the stupid ones are full of confidence” said Charles Bukowski (or maybe it was Bertrand Russell, or somebody else – it is variously attributed). And that seems right.

The problem with all of this is that it is wrong.

Not all wrong mind you. But wrong, at least, as it pertains to Dunning’s research.

Dunning wasn’t studying stupidity. He was studying the effects of competence on self-evaluation. In their initial publication, he and Kruger1 showed that poor performers tend to over-estimate their abilities/performance, whereas high performers tend to underestimate theirs. Their data looks far less exciting than the Mt. Stupid curve:

That finding has been seized-on by people keen to say that stupid people don’t know they are stupid. However, a more plausible explanation is that beginners just don’t know how much they don’t know. They simply lack the perspective to judge their own performance. And the ongoing research from Dunning’s group2 supports this latter interpretation. Decades of research about skill acquisition seem to concur.

Being inexperienced is not the same as being stupid. If it were, we would all be mostly stupid, because we are all inexperienced at most things. It is the human condition. We enter the world with no experience whatsoever and then each of us spends the rest of our life gaining experience in a small number of the multitude of potential human endeavors.

Actually, I would argue that most of us would never get good at anything difficult if it weren’t for the fact we don’t know what we don’t know at the outset. Human accomplishment depends, quite often, on individuals being in too deep to turn back before they realize what they have gotten themselves into. “Oh well, it’s too late now” is the sentiment that links “Oh shit, this is harder than I thought” to “Oh wow, look what I can do!”

The image below appears to be a posting from some social media platform (Twitter, probably), which made it to one of my feeds several years ago. I don’t know whether the original poster was genuine or trying to be funny, but it attained meme status as others circulated it – because it’s funny. At least, it’s funny to me. I am certain it would not be funny to someone who is not a mechanic though. In fact, if you are not a mechanic, you likely wouldn’t see the humor even if I explain the joke to you (the belt is inside-out). But if you don’t get the joke, does that make you stupid? Obviously not. The humor simply is not accessible if you don’t have the perspective that comes from experience and a detailed mental model of a 4-stroke, multicylinder, internal combustion, interference engine. The joke might be there in plain sight, but if you don’t have a perspective from which to see it, then you simply don’t have the perspective to see it. And it would not make you morally superior if you did have that perspective. Mechanicin’ is just one of billions of things human beings can get good at and can develop sophisticated understandings about. But none of us can know or do all the things. If this is not a thing you have put the time and effort into coming to know, it does not make you stupid. It simply means you are unaware. It is fair to call that ignorance, but not stupidity. Ignorance is a state of opportunity. Stupidity is not.

So then Cleese’s summary is nearly perfect, but for a single missing word: yet. People who are not (yet) good at something lack exactly the skills they need to know they’re not (yet) good at it. Beginners lack the perspective to see how much they don’t know. That is the nature of being a beginner. No matter what the domain – teaching, road grading, carpentry, installing septic systems, writing, etc., you learn to walk by walking – and you can’t do that without falling down.

I think it was said best by my colleague, Lisa Hauck, (who has a gift for distilling profound insights into a single sentence): the more I understand the less I know.

I poured a concrete pad for my new heat pump the other day. And it looked like shit. I had seen it done many times before – and I watched a bunch of YouTube videos beforehand. I thought and planned for hours to try to set myself up to do it well. But there were things I didn’t know to plan for (like the very limited range of the cement mixer when it came to pouring). And I was rushed by my choice to use rapid-set concrete mix, so by the time I realized I’d neglected to have all the necessary tools nearby, I didn’t have time to run and get what I needed. I had to improvise. As it turns out, my hand makes a poor trowel. It looked so bad, after it set up, I added a layer of self-leveling, resurfacing mix to hide my shame.

The first time I used my hexagonal collet to cut a bolt head onto the end of a shaft, it looked like shit too. It looked easy when This Old Tony did it. I understood the principle of it. But I didn’t appreciate some of the nuances in getting things lined up. So that first head came out wonky. I learned from that experience though and the second one came out better (still not great, but better). Both homemade bolts work. I made them to hold two heavy things together on my tractor and they continue to do that job adequately. But they look amateurish.

I don’t feel stupid for having made those mistakes though. Incompetent? Yes. Stupid? No. I was inexperienced. I was trying a new thing – two new things. In both cases I just mentioned, I made the classic mistake of thinking it would be easy, because someone more competent made it look easy. A little bit of failure taught me that the person who made it look easy had skills I don’t (yet). It was a little disappointing that it didn’t go well on my first attempt, but it is not surprising. As Jimmy Diresta says, you always go to school on the first one. I overestimated my ability because I did not (yet) know better. Of course, believing I could do it is what motivated me to give it a shot. And now I have both improved ability and a better sense how much work there is left to do before I get good at concrete or metal work. I have a lot of work left to do to get good at either of those things, but I have been schooled by those experiences, so now I am less beginner-y.

The thing is, to say beginners tend to over-estimate their abilities/performance, whereas people with experience tend to underestimate theirs is boring. It is terrible click-bait. Like so much contemporary information, an interesting fact about a difference between novices and experts got appropriated and distorted by someone hoping to recruit interest in their thing. I suspect the details are lost to history, but the storyline is common enough it is easy to see what happened. The Mt Stupid graph above, and numerous examples just like it, have been circulating the internet for years – ever since someone appropriated a different model (possibly the Kubler-Ross change model or one of its descendants) to fit their interpretation of Dunning’s findings. The Mt. Stupid curve is not research-based – not any more than the recent headline claiming we are all eating a credit card’s worth of microplastics each week. It is just wrong.

And yet…

It is a strange feature of truth that we sometimes get there by false paths. The fact that the Mt. Stupid curve is not research-based (as it falsely seems to be) doesn’t mean it is wrong. I think the popularity of the Mt. Stupid meme reveals something else we all know tacitly: while we all face a mountain of ignorance any time we set out as a beginner, some people get stuck on the near side of that mountain. They learn just enough to believe they know it all and then stop climbing. They don’t push far enough into the domain for it to open up to them. They never reach a point to see how much they don’t (yet) know.

That sort of failure of wonder – that willful not knowing – can, I think, fairly be called stupidity. It is learning impairment that is nothing to do with genetic predisposition and everything to do with egoistic predisposition. When capable people stop learning before they gain enough perspective to start seeing how much they do not (yet) know, it is either because the bullshit quotient is too high, or they are humility deficient.

All beginners have to summit a mountain of ignorance before they get good at a new thing. There is a difference between ignorance and stupidity though. Ignorance is simply a state of not knowing – and that is common to all human beings. We don’t know most things. Stupidity, on the other hand, is an inability to learn. And that inability most often results from choices. Not genetics. Ignorance can be overcome. In fact, it is full of possibility for anyone inclined to learn. It is the nature of being human that we spend our lives becoming less ignorant through wonder, play, thinking, and making. Stupidity is an impediment to doing those things – an impediment to being fully human.

Arrogance is only possible for people too naive for humility. Experience can breed humility for those inclined to learn – especially when the bullshit quotient is low. But arrogance can undermine the persistence to gain meaningfully new experience as well. And when that happens, arrogance converts ordinary ignorance into Mt. Stupid.

Getting schooled by experience requires feedback – and attention. The feedback on my concrete pad was very visible. It was literally set in stone. I was embarrassed by how bad it looked – and I didn’t want to have to see it every day. Hence the immediate resurfacing. The bullshit quotient is low when results are so… well… concrete.

The bullshit quotient is high when results are abstract though – and that makes for ambiguous feedback. It is like dense forest undergrowth on a mountain. It restricts your view, so you never really know where you are.

In Academe, there is a shit ton of undergrowth.

One of my favorite movie quotes comes from Dangerous Liaisons: “Like most intellectuals, he is intensely stupid.” It makes me laugh, because I see so much truth in it. Few occupations have a higher bullshit quotient than college professor.

I suppose I should be careful how arrogantly I deride my own profession. I am getting dangerously close to the territory of the hypocrite. And hypocrisy is one of a very few characteristics I detest more than arrogance. Still, few things exhaust me more than trying to coax people up the mountain who are so certain they know better than me that they needn’t find out what I know.

Enough with the pontificatory tangents. Here is my point: Mt. Stupid is not a finding from Dunning’s research, but I think it is a thing. Many people fail to summit the mountain, but it is not because they are unintelligent. It is because they are arrogant. And the higher the bullshit quotient for the task they think they have mastered, the more likely they are never to reach the summit – never to learn enough to glimpse how much they don’t know. Getting stuck on the near side of Mt. Stupid is not a problem of insufficient capability. It is a problem of excessive hubris – and bullshit.

So on the one hand, I think Cleese, and so many others, have missed the mark when they conclude that Dunning’s research suggests stupid people will never realize they are stupid and wrong. As long as the rhetoric is rooted in assumptions about intelligence, then it is simply wrong to say stupidity has anything to do with Dunning’s research – and it is incredibly ironic that so many people proclaim this misconception so confidently. However, there is space for Cleese to be right if stupidity is understood as a inability to learn or understand – particularly if it is recognized to be self-imposed. Impediments to learning are legion: trauma, lack of access, unmet basic needs, Vogons in the front of the classroom – or in the front office, etc. Those things do not reflect on a learner’s intelligence though. Those are all external forces that impede learning – so it would be more precise to say those forces are stupidifying. And such stupidification is unjust and dehumanizing. And we should be critiquing and dismantling institutions that cause stupidification – not blaming the individual victims thereof. In contrast, I do think it is reasonable (and necessary) to critique individuals engaged in self-inflicted stupidificaction. Willful not knowing is, properly, stupid.

And this all leads me to what I think is the important lesson of Mt. Stupid: for domains in the which the bullshit quotient is high, arrogance causes stupidity. Arrogant folk stop climbing the mountain of ignorance before they gain the perspective to see how little they know – wrongly interpreting their failure to understand other people in the field as evidence of their own superiority. Hubris is a massive impediment to learning and understanding – and in that sense, it is self-inflicted stupidification.

To be clear, I don’t mean to merely moralize about what other people should be doing with their own lives/capabilities. I don’t have a problem with people choosing, for themselves, not to learn a thing. I am ignorant of all sorts of things – things that I am not trying to learn. It simply couldn’t be otherwise – I cannot learn everything. But there is a difference between relying on other people to learn the things I can’t know and disregarding what other people know. The problem with getting stuck on the near side of Mt. Stupid is that people too arrogant to finish the climb tend also to be too arogant to get out of others’ way. Their stangnance becomes an impediment to climbers who are genuinely trying to learn. And they hold other people – the ones with the humility to strive for excellence – back.

The problem with the world is that arrogant people accumulate on the near side of Mt. Stupid – too far back to see the good work on the far side – creating a barrier for those starting the ascent while also acting as ballast and belittling the work of people who actually know what they are doing. That is stupid. Or, more precisely, the roadblocking result of accumulating arrogants is infuriatingly stupidifying.

______________________

1) Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134.

2) Sanchez, C., Dunning, D. (2018). Overconfidence Among Beginners: Is a Little Learning a Dangerous Thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(1), 10-28.