|

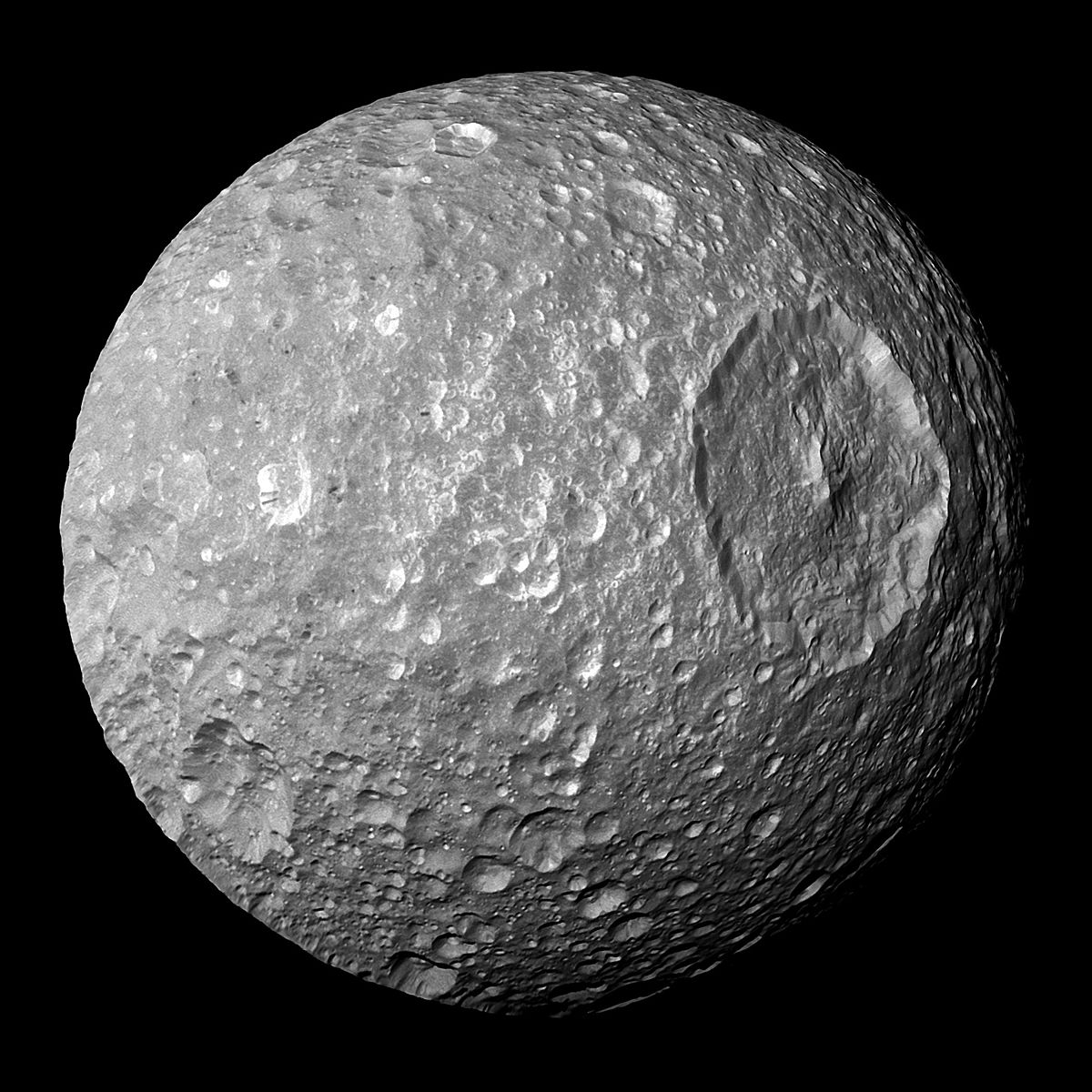

| That’s No Moon |

In next month’s issue of Icarus, a group of geological and astronomical scientists argue for moons and planets to be classified within the same category. Maybe that seems like the very definition of tedium, but I think it is actually a fascinating look into the fallacy of reification, the human capacity for mindlessness, and the deliciousness of irony.

There is no scientific reason moons and planets should be thought of differently – most of them anyway. But they are. I think of them as different things. Why wouldn’t I? They have different names. It only seems logical that they would be different. It only seems logical – if you don’t really think about it. It turns out I probably shouldn’t mindlessly think of moons as being different from planets. Of course, I am not an astrophysicist, so I don’t often have reason to think about it. Also, the consequences of my thinking about it one way or the other are relatively trivial. But it seems like the kind of thing space scientists would fuss over quite a bit. It seems like it would matter to them quite a bit.

The authors of the paper in Icarus begin by pointing out that taxonomic systems, like much of scientific knowledge, are theory laden. The ways we categorize the parts of our world are as much about how we think about our world as they are about the things in the world themselves. We name and categorize things in order to think and communicate about them. But the names and categorization schemes we use also tell us what we think. For example, to categorize a dolphin as a mammal, rather than a fish, says quite a bit about how we understand biology and how life works. Living things could be organized into any of thousands of other classification schemes though. We could, for example, categorize bottle-nose dolphins, orcas, swans, sawyer beetles, and hammerhead sharks as members of a single group: animals whose photos can be printed without a color ink cartridge. There are probably even situations in which that could be useful (e.g., teaching young children about colors or producing inexpensive books), but it is hard to imagine a scenario in which it would help us better understand something fundamental about our natural world. For scientific purposes, it does seem more fruitful to think of fish and mammals as separate categories – but then we have to decide which one includes dolphins. That way of categorizing is deeply rooted in beliefs about what science is, assumptions about how it works, and understandings about how life evolved on Earth. Even so, that does not mean fish and mammals really are natural kinds. Indeed, after a lifetime of study, Stephen Jay Gould concluded there is no such thing as a fish. There are no SKU numbers or bar codes printed on animals to locate and cross-reference against a master catalog to find the truth about how they should be classified. We came up with all the categories and all the names ourselves. We keep using them as long as it seems fruitful to do so – and sometimes even longer. But fruitfulness doesn’t mean it is right in any sort of absolute sense. Ask a Platypus.

Similarly, moons and planets are not natural kinds. They are treated separately by convention. The paper in Icarus traces the history of that convention – and, as it turns out, the history is more telling about human beings that it is about the nature of the universe itself.

From the Copernican revolution, scientists treated moons and planets as being in the same category. They are not just big rocks. They are huge hunks of stuff, massive enough for their own gravity to hold them in a roughly spherical shape, which go around the sun in regular paths, absorbing and reflecting energy from the sun, but not producing their own energy. In our solar system, for example, we know of 8(ish) primary bodies that fit this definition (i.e., planets). We also know of numerous secondaries (i.e., moons), which each orbit one of the primaries in addition to orbiting the sun. That makes their orbit around the sun a bit loopier than the primaries – but only a bit. If you believe Newton’s Third, the primaries also orbit the secondaries. They are all wiggling along periodically as they orbit. And then there are dozens of other diminutive primaries, like Pluto, that scientists were squeamish about including in the same category as the 8 bigger ones. But they are squemish for social, not scientific, reasons.

There isn’t really a good scientific reason to put the primaries and secondaries in different categories. In fact, if we were to consider the physical make-up or properties of the various bodies, the Earth (and other terrestrial planets) more closely resemble several of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn than they do the gas giants themselves. I suppose it could be argued that the 8 primaries have something in common because they all orbit the sun in the same plane, suggesting a common origin within our solar system, while Pluto and many of the secondaries orbit in different planes, suggesting they originated elsewhere and were captured by our solar system. Of course, many of the moons and asteroids in our solar system also orbit in the same plane as the planets, so the common-plane thing is not a particularly convincing argument. Also, it seems more than a little anthropocentric to segregate stuff that originated here from stuff that originated in any of the other billions of solar systems out there – especially when we are operating on a basic assumption that they are all made of the same stuff (i.e., the same ~100 elements), are governed by the same physics, and had the same ultimate origin. Indeed, the western scientists that developed modern astronomy, from Copernicus, to Galileo, through the European enlightenment and up to the beginning of the twentieth century, did consider planets and moons to be part of the same taxonomic category.

During the 19th century, a rift started to develop between the way the scientific community classified these things and the way the general public did. Astrologers, it seems, considered moons and planets to be different things. As enlightenment thinking started to displace them from being learned advisers of privileged classes in Europe, astrologers integrated into other layers of society. Consequently the meanings that astrologers ascribed to moons and planets emerged as a folk taxonomy and became common in non-technical writing around the 1850s.

The scientific community continued to treat primaries and secondaries as being in the same category until the community lost interest around 1920. Presumably they were too enthralled with sexy new ideas like quantum mechanics and relativity to spend time with their telescopes. In any case, by the time space exploration became a thing and interest picked up in sending probes to visit other parts of our solar system, the scientific community was a couple of generations removed from the taxonomic debate and the folk taxonomy was the one in widest use. So mid-20th-century scientists simply picked up the folk taxonomy. They treated planets and moons as different things, because they had different names – and nobody asked why.

This is all detiled in the Icarus article – you should check it out, its a fascinating read.

In any case, things came to a head in 2006, when Neil deGrasse Tyson famously presided over the demotion of Pluto from planetary status. The meaning of the word “planet” had apparently become too ambiguous. So the International Astronomical Union decided to make it biguous, voting to adopt a precise definition. And Pluto got relegated. To be clear, it was the definition of “planet” they decided. They were not just picking on diminutive Pluto – it was just at the wrong place at the wrong time. Astrologers only had names for a handful of planets – and if scientists adopted a definition that permitted Pluto to be a planet, they would have to admit dozens of other objects as well. So, instead, they chose a definition that wouldn’t require astrologers to come up with so many new names. Pluto’s relegation was a consequence of adopting the new definition. Lots of people were involved in the vote, so is mostly unfair to blame NdGT about Pluto’s fate. It’s funny when Sheldon Cooper does it though.

In any case, the authors of the forthcoming article argue the IAU made an odd choice, basing their definition on the folk taxonomy. They suggest a return to a definition that would include moons as planets because it is more scientifically meaningful. Some astrophysicists are a little nervous that changing the definition again could re-open the oddly rancorous debates about Pluto. I disagree. Pluto has a shot to be promoted back to the premier league. How exciting!

Nerdy drama aside, I find all this fascinating for a couple of reasons. One is that, the authors of the paper have to point out the theory-laden nature of taxonomic systems to their audience. Actually, come to think of it, they don’t just point it out. It takes them almost a whole page to make and justify the point. They put a lot of effort into reminding the scientific community that all of the words are made up. All of the words we use – someone made them up. Regardless how good the reasons are for believing they symbolize important things or processes, or how useful they are for achieving inter-subjective understandings, the patterns of buzzes, clicks, and pops (or lines, spaces, and squiggles) that we call words are, themselves, arbitrary. That should probably seem obvious. So it says something about an audience, when a page of academic text is needed to make and justify the point. We made up all of the words. Which means we made up all of the categories. That is not a bad thing. It doesn’t make them wrong. It is just something important to be mindful of – and its probably a bad idea to pretend it didn’t happen.

Many natural scientists are pretty invested in the idea that they are discovering how nature works – as opposed to constructing an understanding of how it works. So they tend to bristle at the suggestion that their concepts or categories were human creations. There is a complex history in this. Several different things are going on. The epic myth of individual scientists heroically making nature reveal her secrets stokes egos. A narrow definition of objectivity allows scientists to believe it is possible, even desirable, to achieve a perspectiveless perspective. But apropos of the saga of moons and planets, there is a strong legacy of non-scientific ideas, first taken up nearly 4 centuries ago, which is still mindlessly perpetuated in scientists’ discourses.

Descartes and his contemporaries assumed that their investigations of the natural world uncovered the facts of God’s creation. This is why, for example, precise (mathematical) descriptions of reliably observable patterns in nature are called laws. Circa-1620 scientists believed that, when God created the universe, he set rules for it to follow (or, at least, they professed as much to inquisitors). Thus, when regular patterns were observed in the universe (e.g., regularities in the movements of heavenly bodies like stars, planets, and moons) it was assumed the reason for the patterns was that the objects were obeying divine laws. So that is the name they were given. The quest for certainty – the idea that scientists uncover truth about the nature of the natural world – is rooted in a belief that divine will is responsible for (and, consequently, there to be found in) the objects and processes of the world.

Surely, the contemporary scientific community would disavow a belief that the observed behaviors of planets was due to divine regulations on cosmic traffic. But just like they didn’t ask why moons and planets have different names, they typically don’t ask why we call certain equations “laws”. They just take up the words, assuming they refer to something meaningful. It is a logical fallacy to do this – the fallacy of reification. And people do it all the time. And scientists are people too.

What I find fascinating, from a sociological standpoint, is that scientists have come to think of themselves as immunized against being misled by superstition or anecdote, because their quest to uncover the divine intentions in the universe – the universe as it truly is – affords them an objective standpoint that is somehow unpolluted by human subjectivity. But that is exactly the sort of magical thinking they purport to be rooting out. Their commitment to the belief they are uncovering universal truths is rooted in a decidedly non-scientific (i.e., theological) ontology. Ironically, the insistence on closing their eyes to their own human nature opens the door to having their theories infiltrated by – indeed grounded in – the vestiges of the very kinds of ideas they eschew. And it takes a full page of academic text to remind them the words they use are all made up.

The second thing about the forthcoming paper that is fascinating to me – and this is the part that seems like a Monty Python sketch – is that, when the scientific community decided it needed to define “planet”, they relied on ideas from astrologers. This is funny to me, because it has only been about a century since Popper became grumpy about how frequently the term “science” was being misappropriated as a way to confer greater credibility to all sorts of things that didn’t smell anything like science. His strategy for clarifying the demarcation criteria, was to compare some examples that any competent thinker about science would surely consider scientific with other examples that, while they might bear some superficial similarities (e.g., they are data-based), competent thinkers would surely see as non-science (i.e., pseudoscience). His exemplars included some of Albert Einstein’s work. Obviously and uncontroversially, exemplary science. And his counter-examples, the ones that are clearly and uncontroversially pseudoscience prominently featured astrology. And since then, while a precise and universally accepted definition of science is still evasive, astrology remains one of the most commonly cited examples of what science is not. Astrology, in short, is unambiguously the antithesis of science.

And yet….

When the scientific community decided they needed to settle on a definition of “planet” they reached for ideas from their antithetical exemplar.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Well… the Python’s could.

And Douglass Adams.

And Kurt Vonnegut…

Come to think of it, I guess lots of people have made-up stuff like this. Pretty much any satirist who has written about science.

Richard Feynman disliked philosophy, especially philosophy of science, because he considered it so much worthless beard stroking. Is it? I mean, I get annoyed with people who think themselves into believing nonsense – who get so caught up in their own bullshit that the circularity of their reasoning justifies its own disconnection from reality. And I have no patience for intellectuals who make a sport of making simple ideas incomprehensible. A lot of western philosophy is tilting at windmills. But surely, ignoring philosophical questions altogether is not a better approach. Mindlessness, afterall, leads to outcomes like defining key terms of your field based on its literal antithesis. Some reflection is good.

Kudos to Metzger et al. for holding up a mirror.