Ascribing a name to something makes people feel that the object, so-named, is a real thing – and importantly thing-y in some way.

I suppose I had noticed this phenomenon before, but something crystallized while I was sitting in a research presentation of an early career scholar a few years ago. I think she was presenting her dissertation project. (Aside: I don’t know for certain. She didn’t say so. And it is hard for me to articulate whatever tacit or intuitive sense made me think it was a dissertation project. There was a slight stiltedness in the way she worded particular minutia – or maybe it was a slightly pedantic attention to too many details that suggested an advisor, or other committee members, had gone looking for nits and picked at them incessantly. I’m not sure. But, one way or another, it was a well-conceived and well-conducted study – if a bit immoderately detailed.) I was at a fairly large conference, which is always populated with lots of presenters I am excited to see. But it is also one at which the quality of presentations tends to be… er… uneven. So it is always tricky to decide which sessions to attend. I have chosen poorly in the past and ended up sitting in a bad session, feeling resentful that I was missing a good one elsewhere – and also trapped because there were too few other people in the room for me to escape discretely. In any case, this particular session was was turning out to be a good one and as I listened to the first few minutes, I relaxed into feeling comfortable with my choice.

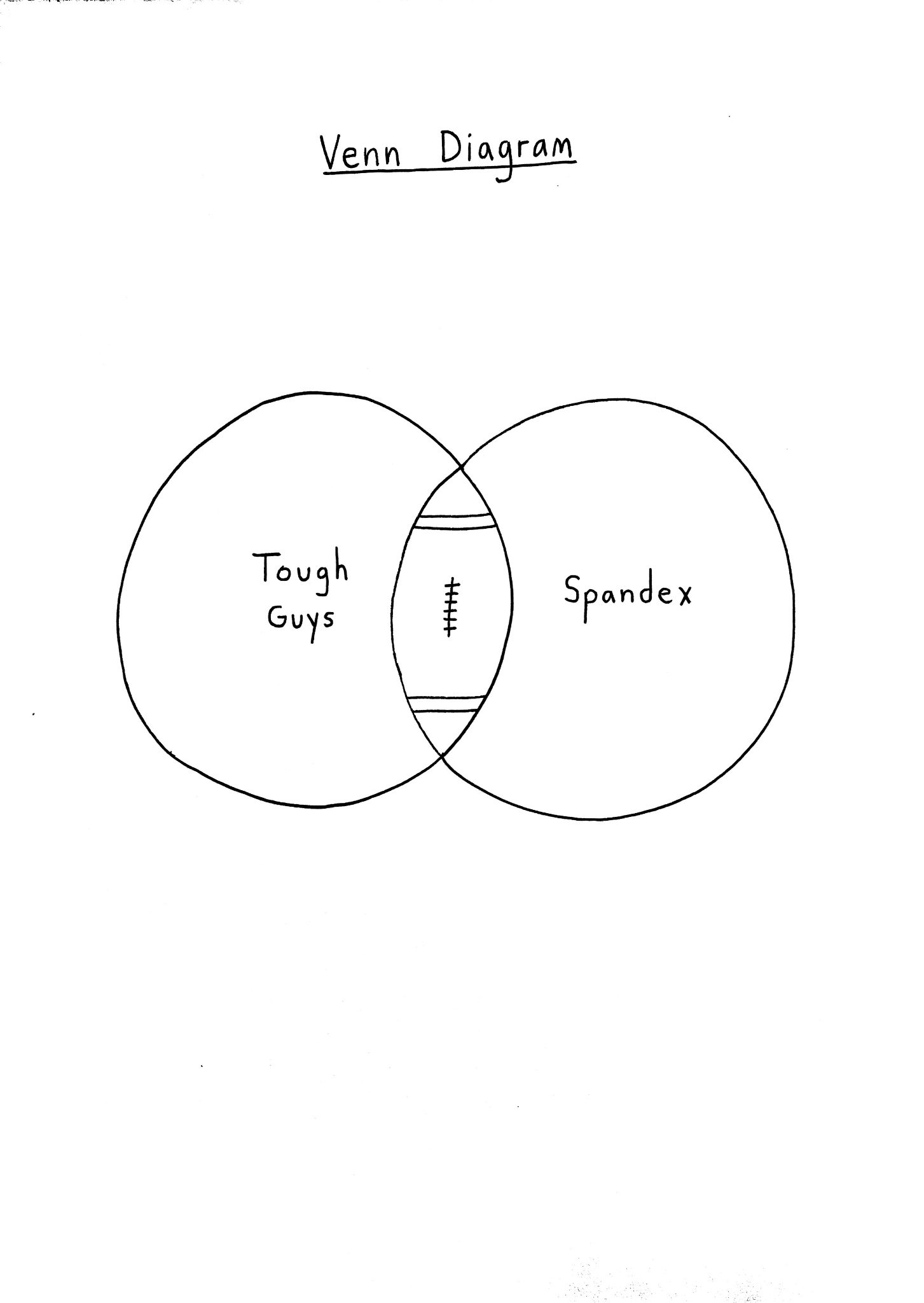

|

| Illustration by: Demetri Martin |

The presenter was thoughtful, articulate, and engaging. So I was a bit thrown when she projected her first table of results and then, before even beginning to discuss the meaning of the information it contained, provided us a rationale for the type of table she had chosen to display the data.

At first, I dismissed it as the sort of detail new researchers include before they learn to separate the wheat from the chaff in communicating information-dense ideas (or is it that they are trying to appear well-informed by using as much specialized language as possible…?). But then she doubled down. She named the type of table she had chosen and gave a citation to the Miles, Huberman, and Saldana text for it.

I have attended hundreds of conference presentations and had never heard someone do that before.

What a curious detail to include. And what interesting consequences. By drawing attention to the fact she had chosen among a menu of display options, she had marked herself as a novice. That was a jolt, because she had definitely seemed far more competent up to that point.

Why make a show of naming the type of table? Names are given to such things for organizational or pedagogical purposes – but few types of tables are innovations that rise to the level of intellectual property. This is not a decision that needs to be cited. The point of a table is to organize information to simplify communication – it is the information that is important, not the container. The presenter was clearly too thoughtful to have confused this superficial detail – the name of the table – with information essential to her study. And yet, here she was making a big show of justifying her decision.

It threw me out. I don’t know that I heard anything else she said after that. After her great set-up, she distracted me with a detail so far out of left field, I missed the punchline. I was off, puzzling over the table-naming thing, no longer listening to her.

This had all of the markings of being the legacy of some teacher’s pet obsession. I would bet money that, when this presenter had been a student, she had been subjected to a rubric that included ‘identify the type of table used to display your findings and provide rationale for the choice.’ Perhaps it started as a well-intentioned goal of drawing students’ attention to the fact that the way data are displayed has an enormous impact on an audience’s ability to make sense of that information – and what sense they make. Perhaps this instructor required students to justify their choices as a way to ensure they were intentional about their choices in order to communicate their findings clearly. That would be all well and good if it were what their students were learning from the exercise. But it clearly was not. This particular presenter had learned dogma: that the naming of the table was somehow a sacred act unto itself.

Enduring structures always preserve marks of the scaffolding used to construct them. Some teacher had indoctrinated this presenter – who was otherwise very thoughtful – to perform a superficial ritual that undermined her credibility. Well-intentioned or not, obsessing over naming and justifying display choices endured in this presenter in a way that was harmful to her and the point she was trying to make.

We are somehow comforted by having a name for things – even if the name is meaningless. I have heard the word “instinct,” for example, described as a pacifier word. If you were to ask how it is that robins all know how to build a robin’s nest even though none of them ever teaches others to do it, the answer you would most likely get is that it is an instinct for robins to build a nest that is characteristic of robins. Other birds have instincts to build other kinds of nests. People are usually pacified by that answer. We discover that lots of animals do lots of things instinctively. However, if you were to ask what is an instinct, the answer is that it is a behavior animals do without needing to be taught. You can get more technical, if you like, and point to the fact instincts are species specific as an indicator of genetic inheritance and evolutionary selection and whatnot. But, at the end of the day, to explain it as an instinct is tautological. To say that robins have an instinct to build robins’ nests is to say that robins do a thing without needed to learn it because it is a thing robins do without needed to learn it. To call it an instinct does nothing to answer the initial question. But we accept it as an answer. “Instinct” is a meaningless word. But it make us feel better to have a name for an otherwise inexplicable thing, because we don’t have to think (or wonder) about it anymore.

(‘Nuther aside: I keep saying “we.” I am not entirely sure who “we” is though. I am not sure whether reification makes all humans feel better or just a subset I am part of. Very probably it is a Western thing. We are, afterall, obsessed with intellectualizing everything. We are all, to some extent, disciples of Plato and his elitist presumptions about the stuff that happened in his head being superior to the stuff that happened in other people’s hands. Naming things is also a way of claiming ownership of them – and we Westerners do that obsessively too.)

This is not to say that reification is a bad thing. Wenger says that communities of practice make meaning through an ongoing, dynamical interplay of reification and participation. That is, we reify aspects of our shared practice as policies, procedures, forms, routines, taxonomies, names, etc., so that they can make shared understandings a focus of joint attention. They help members of a community see what behaviors are sanctioned and they concretize the values of the community. But those reifications are always incomplete – and they do nothing on their own. A policy, procedure, form, or whatnot doesn’t have agency. It has to be enacted by someone. And enacting a reification is what Wenger call participation.

Reifications matter because they shape the ways that individuals participate in the community. But they do not dictate behavior. Individuals often have to improvise the ways they enact particular reifications as they encounter new or unexpected problems not directly anticipated by existing reifications. In other words, participation is always bricolage. The way communities of practice evolve over time is that individual members encounter new problems which require them to improvise the ways they enact existing reifications – and that new form of participation changes the ways the community understands those reifications (which shapes the ways the are enacted and so on and so forth). For example, the ways a policy is implemented usually changes over time, as new situations arise. As decisions have to be made about how to interpret the policy in the context of a novel situation, the meaning of the policy shifts and it gets applied differently in other situations as well. Policies evolve through an iterative process of implementation and reinterpretation. Eventually, old policies are so out of step with the actual practices of a community they have to be revised (or eliminated), and the new policy begins to shape the practices of the community along a new trajectory as members participate in its implementation. This is a basic nature of all complex systems.

The problem with reification arises when it becomes and end unto itself. It is a problem very parallel to religious fundamentalism, which occurs when believers turn their ritualistic worship away from those things that are worthy and toward the rituals themselves. This is appealing for it’s absence of ambiguity. The rituals themselves are concrete and fully specified (i.e., reified), so it is easy to point to exactly what is being worshiped as sacred. Effectively, it absolves the faithful of their need for faith. And it is a form of idolatry.

To make reification an end is also an initiator of death. As Wenger stresses, meaning is negotiated dynamically. The pairing of reification with participation is not a dichotomy. It is an duality. Bruner might call it an antimony. Palmer might call it a paradox. However you label it, one pole cannot meaningfully exist without the other – and neither extreme is tenable. In complex systems, dualities are stabilizing feedback mechanisms. However, when one side of an duality stops functioning, the system quickly diverges toward either stagnation or chaos – two different forms of systemic death.

Historically, the worst human atrocities have been associated with authoritarian attempts to control reified meanings of religious beliefs – to homogenize beliefs and behaviors so that improvisation was prevented. Throughout recorded human history, this is how isolating boundaries have been created between “us” and “them” – and how good people have been recruited to justify exterminating “them”.

Perhaps this seems like a dramatic turn in an essay that started out puzzling over naming a data table. A taxonomy of tables is not likely to lead to genocide afterall. However, there is a type of epistemiced going on here. It is a form of death driven by academic ceremonies that deify the reifications (like the names of categories) and distract attention away from worthy aims of better understanding our world(s). The presenter of the session I attended had worthwhile things to say – but they got lost in the ritualistic recitation of the name of her table. The superficial ritual was an impediment to achieving the scholarly purpose of the presentation. Participation in our collective work, as scholars, was impeded by shifting focus to superficial dogma.

Dogma, be it religious or academic, is comforting, because it absolves people of a need to wrestle with hard questions. It absolves thinkers of their need for thought. It eliminates wonder. As such, reification can be an effective pacifier. Constrained to function on its own, it is also a harbinger of the death of meaning.